|

Support CatholicBoy.com! |

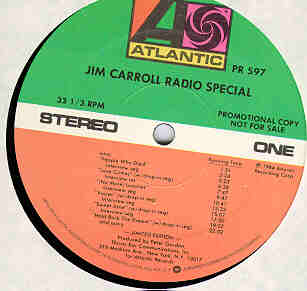

The Jim Carroll Radio Special

Letter from Atlantic Recording CorporationDear Radio Folks, Enclosed is a copy of the Jim Carroll Radio Special, a words and music program produced by Thirsty Ear Communications for Atlantic Records. This 45 minute interview special focuses on one of contemporary rock & roll's most talented poets, who has evolved into somewhat of a "cult hero" on the college radio circuit. Here, Carroll offers insight on tracks from his recently released Atlantic album, "I Write Your Name", which you should have received by now. He also discusses some personal background, ranging from his harsh New York City upbringing (as detailed in his collection of poems, "Basketball Diaries") to his reclusive days in California. For those stations who are relatively unfamiliar with Jim Carroll and his work, this program serves as an excellent introduction to the artist, while stations who wonder, "what has Jim Carroll been up to since he recorded 'People Who Died'" will discover that Jim's talents as a songwriter are merely the tip of the iceburg. A representative from Thirsty Ear will be contacting you soon for the date your station will be airing the Jim Carroll Radio Special. If you'd like to arrange a 12" record giveaway in conjunction with the special, please contact Gene Lanzoni of Thirsty Ear at (212) 697-****. Transcript of the Radio Special"No More Luxuries"CARROLL: Most people think that my life ended after I finished the last page of The Basketball Diaries when I was 16. When they come up and like get into the dressing room or something, get backstage, they always are expecting me to whip out a bottle of Carbona or a bag of glue or something and ask them if they want to go get high up on the roof or something, you know. They don't realize that my life kept going on, you know. COMMENTATOR: Like his old friend Patti Smith, Jim Carroll came to the rock 'n' roll world through an unusual route. He established himself first as an accomplished poet. His first book of verse, Living at the Movies, published when Carroll was 22, was actually predated by an earlier and perhaps more notorious work, The Basketball Diaries. This book was written between the ages of 12 and 15 and is a tough, uncompromising account of Carroll's coming of age in the streets of New York. The book was critically acclaimed, but the most remarkable accomplishment was that Carroll emerged from his ordeals alive. It was these experiences, living on the edge, that were detailed in Carroll's first hit recording, "People Who Died." Now, with the release of his third album I Write Your Name, Carroll chronicles his involvement in the world of rock 'n' roll with the same determination that earned his stature in the literary community. In this program, we'll hear Jim Carroll recount a few of the grim details of growing up, and we'll also hear selections from I Write Your Name. But first, Jim Carroll reflects back on the reactions to "People Who Died." "People Who Died"CARROLL: "People Who Died" was an important song to me. I hate when people think of "People Who Died" as a novelty song--some people refer to it as a novelty . . . I don't see any novelty to it, you know. It's not like--they only think of it as a novelty song because it kind of is off the wall, and people hadn't dealt with that before, you know, in songs, you know. And, um, it got me a lot of flak in certain ways--it kind of permeated the rest of the album. You know, I remember this one article in like the Daily News here, about that I was like the new leader of the death cult in rock, you know, since Jim Morrison was dead, and they kinda were comparing "The End" and "People Who Died," and you know, a lot of people took it to be negative. I remember a lot of people, when they were just playing Beatles songs and Lennon songs after Lennon got shot, a couple people put on "People Who Died," you know, and they got a lot of flak for it. But they couldn't see that it was a song about, you know, stolen possibilities, about people who died young before they could fulfill their promises, you know? "Love Crimes"CARROLL: Well, "Love Crimes" is a song about three different characters, actually. Each verse is about a different love crime. You know, one guy is a hustler on Times Square, and he thinks that love's a crime. And the first one's about some girl getting pregnant and the scene with her old man about having a baby or not. And the last one is just the old love triangle scene. You know, I just thought it would be interesting to write a song about little love crimes, you know. "Love Crimes"CARROLL: The Basketball Diaries, you know, it's written in this real loose diary style about just growing up in New York, all the different changes I was going through. I was really into basketball when I was young, like a lot of kids in New York, and I was like All City by the time I was a sophomore in high school. The first three-quarters of the book are about more or less experimenting sexually and with drugs and stuff, you know.It takes place from about '64 to '67, you know. The hippie scene was blossoming, but I liked certain aspects of the hippie scene, but I could never get into it completely myself--I had too much of a like a tough neighborhood background somewhat, so, you know, so. It wasn't a book about that period, and everybody expected since it took place during those years that it was kind of a hippie book. That's why I waited to publish it until like '79, because, you know, I saw the punk scene happening, and it was a lot closer an affinity to what I was into when I was younger, you know. I mean I kinda was doing the same things when I was about 13, 14, you know. I wasn't into acid so much as hard drugs and stuff. "No More Luxuries"CARROLL: "No More Luxuries," it's about how there's no more luxuries around with Reaganomics and everything--about this guy and girl who just realize they've lost everything but they're gonna stay together. So it plays off really funny lines with serious lines. That's okay for a video, you could do something with it, but my usual like bitch against video is that to me a lot of people are writing specifically for video now, writing their songs, and that's a bad thing to do because once you have one of these things in your head, video, you can't listen to it on a radio anymore, in a car or something, driving along, without just seeing that damn video in your head, you know. Now some of them it could work with, you know, but for what I do, if other people are writing songs for video, I still think that you should write it for the radio because people still have the capacity then to make it their own. "Voices"CARROLL: You know, we all hear the voices from inside of us. After a while they start to haunt us, too much sometimes, some people; that's when you start moving closer to the edge, you know. And I'm just speaking about different situations where these voices come to these people and in what form. "Voices"CARROLL: People ask me how I got into writing, you know, and I really don't know because I didn't have any kind of, you know--I come from three generations of bartenders. And you know, I had absolutely no artistic connections in my family at all. My father used to like run beer for Dutch Schultz during Prohibition. And so there wasn't that much--you know, my parents would get horribly upset when--the mailman for our building, he was a regular in my father's bar, and he'd be delivering poetry magazines there and stuff, and he'd go in the bar and start, you know, talking to my father: "What's with your son? He's growin' his hair long, and he's got this thing happening with, what's he write, poems? Or he reads poems?" And my father would come home half loaded and wallop me, you know, because, you know, "You're taking away my customers!" You know, "Nobody wants to go in a bar of the guy who's tending bar when they know his son is a wimp!" So I said, "I'm not a wimp! These same guys were always clipping out articles about me in the Times about scoring 45 points a game, and stuff, you know. I'm just making a little change here, Pops, you know?" And he'd wallop me again and say, "No changes!" So I kinda split for a while, you know. But um, you know, that all worked out okay. They kinda saw after awhile when I started to get some kind of recognition as a poet, then they thought it was hunky dory. When I started to make some bucks, like from The Basketball Diaries and from records and stuff, then they thought it was really hunky dory. You know, they were hinting for a house in Florida. "Sweet Jane"CARROLL: I was there practically every night when the Velvets . . . right before they broke up, for the whole summer at Max's Kansas City live, I was there practically every night. In fact, there's this record, Velvet Underground Live at Max's Kansas City, which I kinda recorded. This girl, Brigid Polk, from the Warhol scene--I was working up there, and they all hung out at Max's then--I was holding the mic on the little Sony, and that's the tapes that they used for this record, you know, and you could hear me like ordering drinks and trying to score pills in between songs, you know. People always wondered who that was, and it was me. CARROLL: The first thing everyone's gonna accuse you of if you're like a published poet going into rock 'n' roll is pretentiousness, you know, and, you know, I tried really hard to avoid that, and I definitely didn't want to write music with poetry. You know, I tried very hard to write songs with good lyrics, whereas . . . the difference would be technical. You know, when I write a poem on the page, I have to use like certain techniques, like short lines to slow it up and long lines to speed it up, you know, the projective verse idea of poetry, where each line is like a single breath unit. With music, you know, I didn't have that problem, because the music's right there along with it, and they're gonna hear it played rather than read, you know. So, you know, you could be freer with rock and I use more rhymes and stuff, 'cause you know, you use a certain rhyme that hits just when two power chords are changing, and you know, it has this cross-current power like this counterpoint to it, you know. And that was what was important with me, and I saw in that sense it was different than writing poems, and I didn't want to write poems, recite poems and have music. I wanted to write lyrics that were integral to the music. "Hold Back the Dream"CARROLL: Well, actually, this is my personal favorite song on the record, "Hold Back the Dream." It's a song I wrote with a guy from San Francisco named Brian Marnell, who was in a group called *** with Jack Cassidy. He died three months after we wrote the song, unfortunately, which is horrible. But the song specifically, "Hold Back the Dream," is about being so overwhelmed by dreams sometimes, and I also, in just a personal situation, it was at a point in my life where I was so living inside of my head and my heart that I felt out of touch with my body completely. I fell in love with someone, and I realized I had no connection with my body anymore, you know. It was a dilemma. You know, what I'm saying is you have to like hold that back. You can live so far in your mind and out of your body sometimes that you have to push back the dreams. COMMENTATOR: We'll be right back with Part Two of the Jim Carroll Radio Special. COMMENTATOR: And now, Part Two of the Jim Carroll Radio Special. "Freddy's Store"CARROLL: "Freddy's Store," it's about mercenaries. And it's a song about a guy walking into a numbers joint. I know this place uptown, it's a numbers joint--they got slot machines if you walk in to the left, and they got Pac Mans to the right, and there's kids and old men in there, and I wondered, there's so much goin' on in this place that's illegal that I wondered if I just went downstairs what would be there, and I decided maybe there'd be some huge mercenary army training center down there, like. That's the way the song is, it's about falling down the hall, and just finding yourself with this guy who's walking you around, saying, "We've got every gun beneath the sun, we got the space to train, but you don't know you'll learn." "Freddy's Store"CARROLL: Day to day growing up in New York to me, obviously it made me a bit cynical and a bit jaded because I had kind of had a lot of experiences by the time I was a certain age, and it also made things a lot easier, you know, because I got kind of all of that out of my system by a certain point. So when I went to California, I kind of went through this real recluse period, and I felt none of that anxiety about, boy, I'm not in the middle of everything that's happening, like everyone felt during the 70s, you know, "I gotta be there, and I gotta do this, and experience this." I saw that experiencing most of it was either going to wind up being a bore, or, you know, it was gonna turn on you or something, and you were gonna pay twice as much for what you got out of it. So kinda the highlight of my day in California was taking a walk down to the post office with my dog every day for the mail, you know. Usually I didn't even get any after a while, because I never wrote to anybody. I reallyhermitized myself, and I think I haven't changed much since then, since I've been living back in New York now. I'm pretty much you know, a loner and, you know, I don't go out to clubs much and stuff. "Black Romance"CARROLL: "Black Romance" is about just how love can be poison, and how you can be obsessed with someone enough that you're living with them even when you hate them, you know. And you can't lose it, you know, you can't get rid of it. I say in the song, "This is a black romance, there's always one more chance." But, um, the verses themselves are more personal, you know, each one is about a different feeling. It's a feeling of claustrophobia, I think, basically. "Black Romance"CARROLL: I learned after a while that, you know, it's patience and endurance that really makes you break through. It's not like any kind of quick fix, you know. So that was a good discovery for me, and one I couldn't have made if I didn't leave New York and just have some quiet. That's what the thing was. I learned that boredom could be like the greatest tie (?) and I learned the value of silence. "I Write Your Name"CARROLL: It's a song about basically about a guy losing a girl and going around realizing the only way he could get over her or get her back is to write her name everywhere, so he writes her name on bathroom walls in New Wave discos, in San Francisco, on plates, on TV screens, on magazines. He goes writing her name everyplace. By the last verse he gets over her. He becomes a famous graffiti artist, making $10,000 a painting (laughs). "I Write Your Name"CARROLL: You know, in a studio, you use boom mics coming down from the ceiling in a vocal booth, but I'm so used to having a mic stand to grab onto, that, you know, people always ask me after shows, you know, "You must get some bad blisters after shows, because you grab it so tight that," you know, and it's true, I like cut my hands all up, you know, I started to wear gloves after a while. And um, what I'd do was, since I had the boom mic there, I said why don't I just do it in the studio when everyone leaves so I could hold the mic. But then I was making too much noise from that, shaking it. So they just got me a mic stand I could hold onto while I was singing into the boom mic, and I was like getting that same, as if I was doing it live, you know, that same feeling of getting taken out of myself, like I get when I'm performing live, which is the most incredible high of all. "Low Rider"CARROLL: Low riders are these guys who drive around with--they cut their cars real low to the ground, and they move--instead of like when you used to jack up a car to move fast, a hot rod as they used to call them, the low riders jack 'em down real low, and they decorate them, the interiors, incredibly. And, you know they have all these little statues of the Virgin in them. It's a Chicano phenomenon, usually in California. So we were playing in San Jose once, in Fresno, one time, and they were having a low rider convention, so I got to see all thesecars. One of my roadies knocked a bottle of beer from a terrace on our room right on top of this guy's prize car, and he almost died that night--it was great. But it's a song about a girl, an illegal alien coming across the border, and the immigration man shot her 'cause she refused to take a short order. "Low Rider"CARROLL: You know, some people think it's very romantic to reach bottom, but it's only romantic in a traditional like poetic sense, and useful and powerful to your own growth if you rise up out of it, because then, I mean then you can really like have this impact on yourself and on others where, you know, you've virtually started your life over, and very few people, you know, have been able to do that. "Dance the Night Away"COMMENTATOR: We hope you enjoyed listening to the Jim Carroll Radio Special. We'd like to thank Atlantic Records for making this show possible. This had been a production of Thirsty Ear Communications.

|

Site Map | Contact Info | About this site | About the webmaster

The Jim Carroll Website © 1996-2025 Cassie Carter