I was flipping through the Village Voice on Sunday, 8/12/01, checking out listings for the New York International Fringe Festival (an off-off Broadway theater festival), and what did I find? A STAGE ADAPTATION OF THE BASKETBALL DIARIES! I immediately called Jim Carroll, who didn’t know anything about it. . . .

Read my web version of the theater program

Read my interview with Pascal Ulli

On Thursday 8/23/01 and Saturday 8/25/01 I saw Pascal Ulli’s stage adaptation of The Basketball Diaries. Ulli is a Swiss actor who has achieved some acclaim in his home country, having been nominated “best promising European actor” (check out his website at PascalUlli.com). The first time I went to see this performance I felt much as I did the first time I saw the Basketball Diaries film: very curious, anxious, excited, worried. What would this be? How would Jim Carroll be represented? How do you compact that book into a little over an hour? How does a guy from Switzerland translate the book or the experience, literally and figuratively?

The Theater

The St. Mark’s Theater, located on St. Mark’s Place between 1st Ave and Avenue A, is very small. On Thursday I almost walked past it, except that there was already a big crowd of people standing outside. At first I thought all the people were hanging out in front of the tattoo parlor next door, then I saw the sign. (Lenny Kaye also walked by, obviously interested in all the excitement.)

On both nights I attended, the show was completely sold out. Actually, the theater has seating for about 50, but there were probably 55-60 people in the audience each time. You descend a steep set of stairs to enter the theater and reach the performance area, which is located below street level. Inside, there is no stage, proscenium, or curtain separating the audience from the performance.

Seating consists of folding chairs and padded benches lining two sides of the performance area; people seated in the front rows are no more than six feet from the performer. The walls, ceiling, and floors are black (of course), and there are two doorways at the back of the stage: one curtained doorway at stage level, and one glass-paned door at the top of three or four steps.

The Play

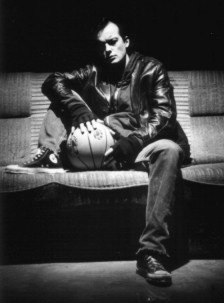

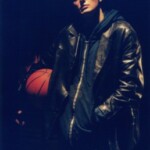

Jim Carroll’s The Basketball Diaries is a one-man play, and the Swiss actor/director/producer, Pascal Ulli, looks something like Leonardo DiCaprio with (dyed) black hair and costume similar to the “street” look you see in the BD film. The set, intended to represent “Headquarters” (the apartment where young Jim Carroll hung out with other local junkies) is minimal: movie posters on the walls (Breathless and A Streetcar Named Desire), a couch, a coffee table with books and a candle on top, a lamp, an overnight case containing various small props, a clear plastic tub that serves as a “refrigerator” or “ice chest,” a trash can (cardboard box lined with a plastic trash bag), and a basketball. The curtained, stage-level doorway represents the bathroom, while the glass-paned door represents both “outside” and the exit to off-stage.

The play begins with the theater darkened and a whispery, prerecorded “voice-over” of an entry from Winter 66: “Just such a pleasure to tie up above that mainline with a woman’s silk stocking and hit the mark and watch the blood rise into the dropper like a certain desert lily I remember I saw once in my child’s encyclopedia, so red . . . yeah, I shoot desert lilies in my arm. . . . ” Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” rises as the voice over concludes “Bob Dylan, he’s in the radio. He glows in the dark and my fingers are just light feathers falling and fading down” (BD pp. 162-63).

The lights come up on Ulli lying on the sofa, reading. He sits up, opens the overnight case, and pulls out a stack of slim red booklets, then addresses the audience: “The more I read the more I know it now, heavier each day, that I need to write,” presenting to the audience the “thesis” entry of the diary (159-60). He opens one of the booklets, starts to write, then pulls out a pocket knife to sharpen the pencil and writes again. This transitions smoothly to, “I’m not as afraid as the bomb as I was a couple of years ago but there’s still plenty of paranoia left,” as he explains that writing is his main reason to hope nuclear war doesn’t erupt (150-51). Ulli flips through one of the red booklets then, addressing the audience, says, “My first entry! How ’bout it? Huh?” When the audience responds, he reads the first entry: “Today was my first Biddy League game,” describing his illegitimate entry into the 13-and-under league and pausing to laugh at “I’m too young to understand about homosexuals but I think Lefty is one.” He flips through more pages, observing, “They all start with ‘today’!” then reads another: “Today [laughs] we moved our last piece of furniture into our apartment in my new neighborhood at the upper tip of Manhattan”; he reads the description of Inwood and its residents, and at “Guys my age strictly All-American, though most of the various crowds do the beer-drinking scene on weekends,” he pops open a Budweiser.

With this entry, Ulli offers a tiny transition of “time goes by” as he jumps into the diary in present-time, now becoming young Jim Carroll reporting on his first day at Trinity: “It’s my first day at the ultra-rich private school that I got a scholarship to come to” (65-66); he relates the complete entry verbatim. Tossing the booklets back into the overnight case, he observes, “I don’t know why the fuck I’m writing this shit,” which introduces the next entry, “If you never do anything to make yourself seen . . . like really seen, the type that makes people point, then you don’t deserve to be seen at all” (89). He punctuates the end of this entry by shooting the basketball into the trash can with a whoosh, then he grabs a bigger Budweiser out of the “ice chest.” He pops it open, sits on the couch, and says, “I never did write about the time I took my first shot of heroin” (30), relating the complete entry. Rolling a joint, he observes, “Junkies are a strange lot” (141), presenting the entry pretty much verbatim up to the top of page 142 (“I’m nodding, no hassles,” becomes “I’m stoned, no stress”). Ulli throws on a leather jacket, jams up the steps, and exits out the glass-paned door. The lights go out and, after a moment, Patti Smith’s “Horses” rises in the darkness.

When the lights come back up, Ulli rushes back in through the glass-paned door, out of breath, sweatshirt hood over his head. He sits on the couch, removes the jacket and the hood, opens the overnight case, takes out a tube of salve, reads the directions, then begins taking off his shoe (Chuck Tailors), methodically unlacing it then unwrapping a long ace bandage. “Oh shit fuck motherfucker I hate cops!” he yells; ” I came within inches of getting my ass tossed in the can tonight. We beat some dopey private school chicks I know for ten beans pawning off a bag of dill weed from momma’s spice cabinet as grass . . .” (143). While applying the salve to his foot (which we in the audience can smell–it’s Ben Gay), he splices in, “I got the word from this senior that the best chicks on the private school scene go to The Professional Children’s School down on 60th St.,” telling about a thirteen-year-old Italian actress he dated (125-26). He pauses, asking, “What was I talking about?” then, “Oh yeah–the private school chicks we ripped off,”relating his close call with cops in the park and completing the entry: “I better get my ass together” (143-44).

This leads into the Pepsi Cola habit entry, where he describes how his small heroin habit has become genuine addiction (121-22); in the middle of it he rushes out the curtained doorway (to the “bathroom”) and we hear him vomiting. He returns, slowly. “I best get out to the country or shit, never gonna make it here. . . . And I used to laugh at the corny monkey phrase too, I had it under ‘control’ all the way to sitting and sneezing a lot on this fucking lice sofa wanting to scream my balls off” (122). Suddenly he jumps up and runs out the glass-paned door, yelling, “Hey, Pedro!” After a moment he returns. Standing and directly addressing the audience, he says, “The narco cops are the most full of shit motherfuckers I know of, and add on the most corrupt too. Like Pedro from 89th, a small time dealer, got snuffed by two of them the other day. . . .” He goes on to describe how the narcotics cops turn in only enough to convict the dealers, keeping the rest to sell for themselves on the street. “So the next time you dudes smoking pipes next to a fireplace in Westchester County ask why the pusher always has plenty of dope to sell no matter how many busts are made it’s because your friendly narcotic agent is filtering the shit right back out to them old street corners before you blink your know-nothing eyes” (128).

Ulli goes to the “ice chest” and removes a lemon, which he places on the coffee table; he empties his pockets, using a pocket knife to cut a slice into the lemon, gleefully shaking a small plastic bag, and taking off his belt. As he sits down on the couch he opens the overnight case again. He brings out a set of works wrapped in a cloth and lays it out on the table. He wedges the spoon handle under the tab of the beer can, squeezes lemon juice into the spoon, dumps in the contents of the plastic bag, adds some spit, then moves the stack of books under the spoon, lighting the candle and placing it on top of the books. He watches it a moment before continuing his monologue: “What ever happened to the old fashioned homo who just wanted to take you home and suck your dick?” He describes some of his more bizarre experiences hustling for money, concluding, “I’d rather go back to ripping off old ladies or something sensible” (104). From here he splices in, “That’s why I’m getting up around six a.m. these days . . . go fishing for early morning constitution freaks up in Fort Tryon Park for sunrise rip-offs,” explaining that junkies resort to this only out of desperation (200). He is silent as he draws up the junk with a syringe, attaches the needle, ties up, and prepares to inject. At that moment a prerecorded, “OPEN UP! POLICE!” rings out, with the sound of banging on the door, and the lights go out.

In the darkness we hear, prerecorded in a voice that sounds very much like the real Jim Carroll, “I am now in Riker’s Island Juvenile Reformatory doing three months for possession of three bags of heroin and a syringe. . . .” (178). When the lights come up again, we see Ulli slumped on the couch in a nod. He wakens, slowly gropes for a cigarette, unsuccessfully attempts to light it, and falls back again into a slump. “Though I’ve only done a month’s time, thanks to the plea of my school’s headmaster I walked out the gates of Riker’s Island yesterday” — Ulli slurs, reaching again for the lighter, this time getting the cigarette lit — “a ‘free man,’ . . . feeling like a . . . cartoon . . . about to run . . . off its reel.” The odor of the cigarette smoke drifts into the audience. He continues in this extremely slurred, excruciatingly slow manner, describing the roach-infested Headquarters as a castle, and, with a friend offering him a syringe of heroin, he confesses, “with the dream in front of me again I found it was quite easy to curse . . . but much harder to refuse.” He jumps to, “So I’m putting this past month behind me for now,” his voice becoming more ragged and angry as he continues, “Suffice to say I am finished with the asshole bandits of shower room rape; suffice to say that those swine for guards won’t draw blood from my ankles again. . . . suffice to say . . . I didn’t become pure on Riker’s Island” (183-84).

After a brief pause, he moves on to “End of LSD era last night” (185-86), painfully slurring his way all the way through this entry describing a bad acid trip. He gradually becomes clearer, although not completely. “Nobody straight with scag down at the poolroom,” he continues, relating his tale about copping four bags of Ovaltine (173-74). He leaves the audience laughing as he stumbles out the paned glass exit door and the lights go out.

Ulli rushes back in as the lights come up. “Shit day,” he says; “I spent a good fucking sick morning trying to cop dope today but not a soul in the neighborhood is holding,” going on to relate his success getting ahold of methadone. “I’ve had methadone before and it takes a good hour at least to hit before you feel them warm oats settling down your sick belly. You bet that’s a long hour too. . . . So then the methadone is pumping that warmth back in me by now and I’m together again, but I ain’t high worth one short nod, the high is all in the past . . . I’m just another normal body now functioning like all the other faces I pass going back uptown though they ain’t laying out bread to get that way . . .” (186-87). Almost seamlessly he splices in, “Like you just know when you’re in the real junkie thing when you wake up in the morning and say to yourself and know it and go through with it, ‘Today I either get my fix or get my ass busted into the Tombs, fuck it all'” (190-91).

The lights go out and flash back on, with Ulli writhing on the couch, wrapped in blankets. “Been up sick for three days trying to kick cold, but the habit has really caught up with me this time and got me licked real nasty. So now’s as good a time as any to lay down just how it feels, though the idea of writing seems like so much bullcrap anyway” (197-98). He picks up one of the red booklets and starts to write, curled almost in fetal position, stopping to sharpen the pencil with his pocket knife, throwing off blankets and tearing off his sweatshirt to reveal a sweat-soaked T-shirt. He tries again to write, then doubles over, rolls off of the couch and crawls offstage through the curtained entry to the “bathroom,” whimpering, “Mommy.”

When he returns, his eyes are rolling around in his head. He slurs, “It’s been about a week now since I put down any entries in this diary, in fact the last one I wrote must have been a bit . . . off key since I had been cold turk three days when I scribbled it down.” He picks up the red booklet and reads, very slurred and slow, “So I’m bundled up here with my coat still on and two blankets too and just when the warmth takes over your body it spreads into horrible flashes of heat flushing on through . . . blah, blah, blah. . . . and to think I have to kick this now because I got to get back to fucking HIGH SCHOOL in two weeks! What a joke, I mean I just can’t believe how . . . unslick I feel” (198). He puts the booklet down. “To tell the truth, my withdrawal only lasted one more day before I shot up a bag of smokin’ stuff I snuck out of Mancole’s coat pocket. Now I’m back as good or bad as ever, hustling around” (199). He continues with the last entry in the book, “In ten minutes it will make four days that I’ve been nodding up here in Headquarters. Haven’t eaten except for three carrots and two Nestle’s fruit and nut bars. But I’ve been slugging away at orange juice all along, anyway, for vitamin C and dry mouth.” As he staggers off the couch, he says, “I don’t even attempt human posture. Think about my conversation with Brian: ‘Ever notice how a junkie nodding begins to look like a foetus after a while?’ ‘That’s what it’s all about, man, back to the womb.’ I’m all thin as a wafer of concentrated rye. I wish I had some now with a little Cheez-Whiz on it. Nice June day out today,” he says, shuffling toward the glass-paned door; “lots of people probably graduating. I just want to be pure . . .” (209-10). He doesn’t end there. “You’ve just got to see that junk is just another nine to five gig in the end, only the hours are a bit more inclined toward shadows” (199), he adds, staggering towards the glass-paned door; opening it, he turns to the audience, says, “As for fear, if you wanna play you gotta pay” (200), and exits stumbling. The lights go out and music rises: “Play with Fire” by the Rolling Stones.

Commentary

When it comes to The Basketball Diaries, I am not a cheap date, as my comments on the Basketball Diaries film should demonstrate. But . . . I genuinely liked Pascal Ulli’s stage adaptation of my favorite book.

I like many things about his performance. Ulli really shows how funny the book is, and he also does a great job of representing the conversational quality of the diary entries (when I read the book, it seems more like Carroll is talking than writing). Because the style is so naturally conversational, the audience may not be aware that almost every word Ulli speaks comes straight from the text (perhaps ten words of dialogue total do not come from the book). Ulli showcases the extraordinary language and style of The Basketball Diaries, which in turn establishes the voice and character of the protagonist. I should note that Ulli is performing the diaries–the dialog comes verbatim from the book, but Ulli is not reading it (except when reading the diaries to the audience is part of the action). In large part, it is the original arrangement of material and orchestration of action that bring The Basketball Diaries alive onstage; these factors also help make this production uniquely Pascal Ulli’s, not just a slavish book-to-stage adaptation exercise.

As OffOffOff.com reviewer Robin Eisgrau says, “Ulli is a very gifted actor and he takes command of the stage here. If you’ve read the book, you’ll find that this production captures the vibrant flavor found on the page. If you haven’t read it, Pascal Ulli’s The Basketball Diaries may make you want to pick up a copy.”

Ulli’s decision to remain true to the text is a playwright’s decision, and I very much appreciate his technique in adapting the book for the stage. The Basketball Diaries is not a linear narrative; although in published form it is arranged chronologically by seasons and years, it is not “truly” chronological. Even Carroll has said the entries can be read in pretty much any order, so there’s plenty of room for a playwright to shuffle things around to suit his or her “take” on the subject matter. Ulli’s mosaic approach to the material works beautifully: not bound by the order Carroll has imposed upon his experience, Ulli tackles the book with remarkable insight and intelligence, finding relationships between entries and synthesizing them in a way one might never think of when reading the book front to back. I object, somewhat, to Ulli’s decision to not end the play with “I just want to be pure,” but aside from that his organization of entries allows me to see the Diaries with fresh eyes. The perceptiveness of Ulli’s approach shines a harsh light on the film adaptation, which rearranges the material . . . much less successfully.

Michael Criscuolo, writing for NYTheater.com, faults Ulli’s production for its failure to define the relationship between audience and performer, pointing an accusing finger at the form itself. Criscuolo argues that the success of a one-person play “rests solely on being thought of by the actor as a full-length, two-person scene between the speaker and the listener, who may be an imaginary offstage figure or the audience themselves. The speaker’s need to tell his or her story to the listener, and his or her reasons for telling it to that particular person, are what drive a one-person show forward.” Criscuolo feels that Ulli fails to define adequately “who his listener is, or what they mean to him,” and that “By doing so, he prevents himself from fully expressing why his character needs to tell his story, and why the audience should even listen to it.” This is an interesting point that seems more relevant to the source text than to Ulli’s one-man play. The Basketball Diaries is a diary, after all, so who is the intended “listener”? Carroll never writes to “Dear Diary”; he always appears to be writing to someone, sometimes addressing his audience directly. But who is the audience, and what is his relation to that audience?

The Basketball Diaries has an explicit thesis that defines the relationship between speaker and listener, but Carroll’s approach in organizing his experience in the book emphasizes the protagonist’s gradual discovery of his audience and purpose for writing. Ulli does not choose this route, nor would he have the luxury to do so. He immediately states the book’s thesis as soon as the lights come up in the first scene: “The more I read the more I know it now, heavier each day, that I need to write” (159-60); this he then morphs into an entry about bomb fear: “I’m not as afraid as the bomb as I was a couple of years ago but there’s still plenty of paranoia left” (150). From the start, Ulli represents his protagonist as a young writer who lives in fear of nuclear annihilation and wants to use his diaries to “wake a lot of dudes off their asses and let them know what’s really going down in the blind alley out there in the pretty streets with double garages” (160). As audience members, we may be either hip “insiders” who know what he’s talking about, or we may be the “dudes” that need to be woken up. Additionally, because Ulli places the “presence” entry at the start, he suggests that his protagonist tells his story as a way to be seen, “like really seen, they type that makes people point” (89), directly answering the actor’s implied question, “why am I writing this shit?” (and also forging the connection between writing and basketball as he shoots the ball into the trash can). Seems clear enough to me. Ulli further emphasizes the original diary form of the material he is performing by letting us see him writing in his diary, sharpening his pencil with a knife, holding up his “diary” and asking the audience if we want to hear his first entry, prompting us for a response, and reading from it, laughing about what he has written. Having established the pertinent details of his character’s environment and motives, he slides smoothly into the book and into the character telling about events as they happen. Ulli’s organization of the first scene of the play successfully brings in many of the most significant historical and personality elements that establish Jim Carroll as an exceptionally smart, funny, and talented young man surviving under treacherous circumstances. All of these factors produce a multidimensional, genuinely human character we like, and whose story we will listen to.

By prefacing the play with a later entry, “Just such a pleasure to tie up. . .” (162-63), Ulli clearly indicates his focus on the drug story of The Basketball Diaries (as opposed to, say, the “birth of an artist” or “fall of an athlete” or “war baby” stories). His treatment of the issue is sensitive and intelligent. However, this performance, by necessity, covers too much territory in too little time and too little space, which is somewhat problematic. The stage set anchors the action claustrophobically in Headquarters, and the entire play runs a mere 70 minutes. Ulli also abridges the addiction process using a “domino effect” shorthand that is far too common in American anti-drug ideology: his character starts by drinking Budweiser, adds cigarettes and marijuana, and before you know it, he’s shooting up heroin and talking about hustling for drug money. Because Ulli’s actions are so casual and “natural,” this domino effect happens almost completely under the radar, and it would be very easy for spectators to miss it entirely. But just when you are getting a good sense of this precocious kid and starting to like him, the downward spiral begins, and it just gets worse. There’s not enough time in the performance for the audience to really grasp what is being gambled and lost . . . or won. Because Ulli spends most of the time as the character “in” the diaries, he cannot simultaneously represent the author writing about his excesses in a state of clear-headed reflection, and thus it is too easy for us not to see the writer developing as the boy descends into the depths of addiction. It’s just down, down, down. If the reviews are any indication, I suspect the American audience is especially difficult because there is so little understanding or tolerance for addiction . . . and those long, slurred, nodding scenes are truly painful to watch. (Side note: the 1999 Zurich production, performed in German and titled In den Strassen von New York, was sponsored by public health organizations.)

Ulli’s focus on the drug story and the limitations of time and space do, indeed, restrict the production to a small sphere. We do not get to know Jim Carroll’s main character, New York City, nor do we penetrate the psychological or artistic depths of the supporting actor, Jim Carroll, as we can when we read the book. The off-off-off Broadway setting lends to the most minimal of production values, with awkward transitions between scenes (lights out, lights on) and a set dragged in from the curb on trash day.

But Ulli’s one-man play, performed in such tight confines, offers something the book cannot: a living, breathing, acting human being, in the flesh, right in front of you. As explicit as The Basketball Diaries is, it is often hard to SEE a real person behind the words; it is too easy to think of Carroll as a fictional character or disembodied narrator. It is impossible to hold such an illusion when watching Pascal Ulli. When Ulli lights a cigarette, the audience smells the smoke. When he applies salve to his foot, the audience smells Ben Gay. We see his sweat-soaked T-shirt. When we see him curled up and shivering on the couch, trying to “lay down just how it feels” to go through heroin withdrawal (197-98), Ulli shows us something that perhaps only someone who has been there can recognize when reading the text alone: an individual in a state of total agony . . . actually writing it down while suffering through the utterly dehumanizing torture of withdrawal. Perhaps my last example is too abstract. Put it this way: on Saturday, when he tied up and prepared to inject with a real syringe, a man in the audience fainted.

Jim Carroll’s The Basketball Diaries is performance in the Brechtian sense, as opposed to classical “theatre.” Some critics have faulted Ulli’s strong accent as a problem in the play (see links below), but I couldn’t disagree more. The accent is a key feature of the performance because it prevents the spectator from sitting back and receiving the representation mindlessly. Although Ulli brings in powerful elements of realism and a dyed-in-the-wool method acting technique, he never attempts to be Jim Carroll, and there is no way the audience can ever just slide into the make-believe and accept Ulli as Jim Carroll himself. The play is a showcase for Pascal Ulli, who has taken the story and words of Jim Carroll and made them his own, creating a multidimensional character who is as relevant in Zurich as he is in New York City. Ulli has put his own unique stamp upon every detail of the play, most obviously in his accent, the poster for [French Swiss filmmaker] Jean-Luc Godard’s film Breathless, and . . . yes, a syringe prominently marked “Swiss made.” The man has a sense of humor, too.

More Images

Here’s a little gallery of official photos (the first two) and photos I took during the experience:

Links

Context: The Basketball Diaries feature page

Pascal Ulli: www.PascalUlli.com (external link)

Interview: Pascal and Caroline Ulli with Brad Balfour and Cassie Carter

Theater Program: Jim Carroll’s The Basketball Diaries

Review: Dan Bacalzo, TheaterMania.com

Review: Michael Criscuolo, NYTheater.com

Review: Robin Eisgrau, www.OffOffOff.com

Review: Les Gutman, CurtainUp